Quality professionals never close the book on betterment. There is always more to do, problems to solve, processes to optimize — and while perfection might be out of reach, improvement never is.

Consultants have a good reason for their nonstop pursuit of near-perfection, too; research indicates that quality improvements, especially those relating to product and design, often lead to better business performance and competitive standing. As one research team noted in an article for the International Journal of Operations & Production Management, “Quality helps a firm gain a competitive advantage by delivering goods to the marketplace that meet customer needs, operate in their intended manner, and continuously improve quality dimensions in order to ‘surprise and delight’ the customer.”

The potential for cost-saving and waste reduction is also notable. Implementing improvement initiatives can lead to fewer product defects, lower scrap rates, fewer expensive recalls, and better consumer perception and brand reputation. In this context, proactively implementing quality improvements to limit operational negatives and enhance positives makes excellent business sense — but is it possible to push the quality envelope too far?

At first, the question seems almost blasphemous. Suggesting that businesses can overdo quality runs counter to the sector’s “perfection or in-progress” mindset; after all, why wouldn’t a consultant pursue an opportunity for improvement if they know it exists?

It’s a complicated decision that ultimately comes down to self-assessment — businesses need to determine whether the value they would obtain from an improvement measure is worth the effort required to implement it. A headlong race towards improvement at all costs can create problems if businesses go too far in their pursuit of incremental improvements that provide limited returns.

Case Study: Busywork at a Manufacturing Plant

Even well-meant quality initiatives can go too far in their pursuit for improvement. Consider a manufacturer that wants to reap the benefits of a continuous improvement culture. As the name suggests, CI is an ongoing, organization-wide effort to proactively seek out and engage in improvement opportunities. Ineffective CI cultures encourage team members at every level to share knowledge and generate creative improvements to processes, tools, products, and services. These changes naturally result in positive changes that benefit the business, optimize operations, and engage employees.

Our hypothetical manufacturer recognized the value inherent to CI cultures and sought to implement one within its own organization. After a short discussion, its leaders implemented an initiative that encouraged employees to identify their pain points and proactively generate solutions and improvements. These efforts bore fruit almost immediately; within a few short months, the manufacturer’s operations had made substantial operational improvements.

Naturally, the organization’s leaders were thrilled. Doubling down on the initiative was a no-brainer; they mandated that all employees make and record additional optimizations. However, given that most large-scale quality improvements had already been implemented, employees were stuck making incremental, low-value improvements such as rearranging their desks or making minor changes to their routines.

The second CI push didn’t provide the value that the original initiative did; in fact, executives noted a negative impact. Rather than viewing the improvement instructions as a valuable effort, employees dismissed the secondary initiative as frustrating busy work — time and effort that could have been better applied elsewhere. This frustration resulted in lower morale and, over time, outright disengagement.

Simply put: the value generated by the improvement initiative was no longer enough to justify the time and effort it required. While quality optimization strategies can be enormously beneficial, continuing to double down on initiatives that have already achieved their goals can and will backfire. Seeking improvement for its own sake is a losing bet; as this example demonstrates, businesses need to execute improvement initiatives scaled to suit their needs.

Guiding Business Self-Assessments with the Quality Asymptote

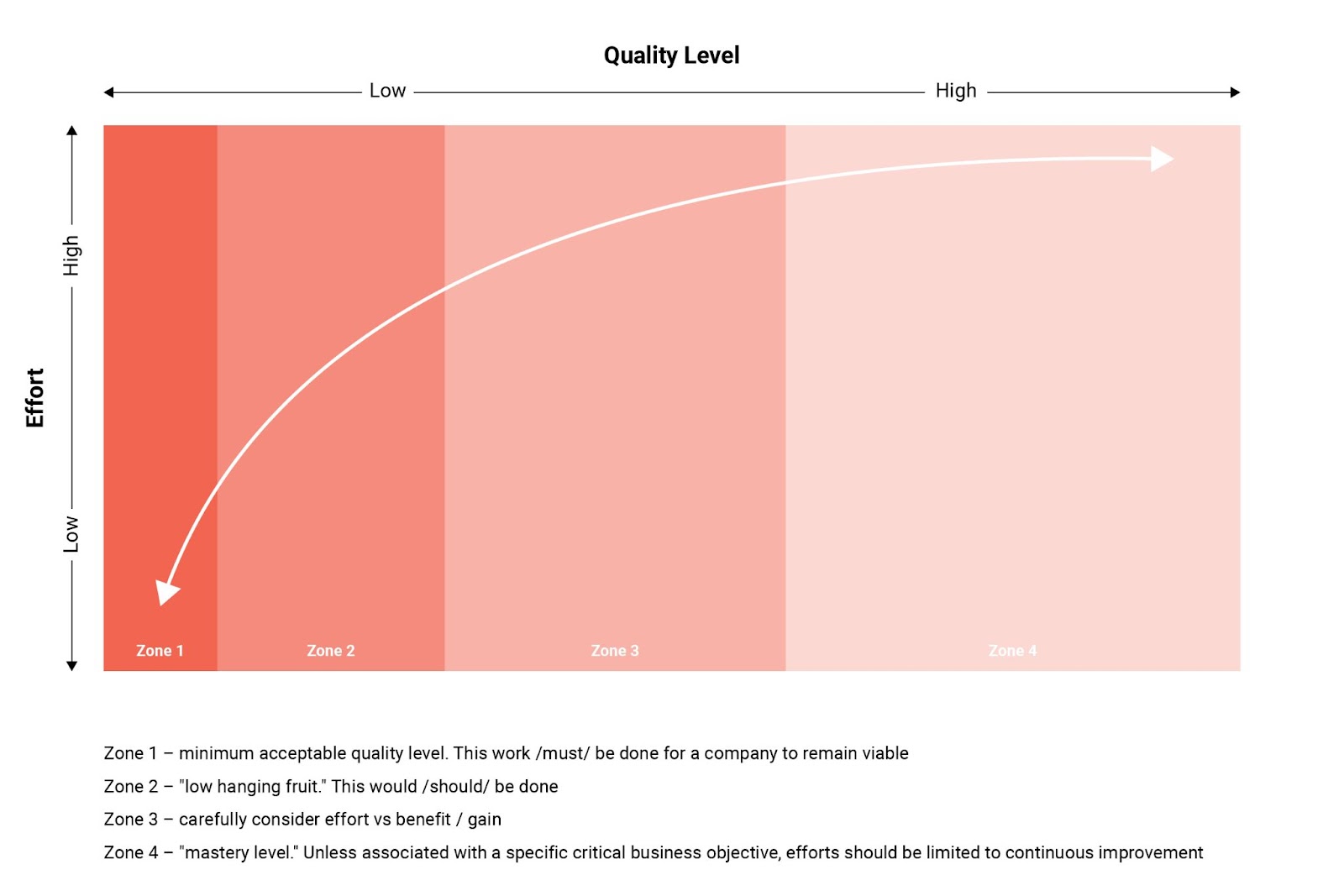

Self-assessment is a crucial part of the quality strategy development process. Before rolling out any large-scale improvement initiatives, executives may want to figure out where their organizations fall on the quality asymptote graph.

The quality asymptote is a curve that extends infinitely along the horizontal and vertical axes, never quite touching either line. The Y-axis represents the effort organizations put into implementing quality measures; the X-axis tracks quality from the minimum permissible threshold to perfection.

The curve, as indicated in the illustration below, is broadly defined into four zones. Companies located in the first zone have achieved minimum quality and thus have the greatest potential for large-scale growth; with a few quality measures, they could see exponential progression along the curve. Businesses in Zone #4, on the other hand, are already nearly perfect and wouldn’t achieve as much value from implementing new quality measures.

Let’s put this idea into a real-life perspective. A middle-school piano student who attends their very first lesson has little skill but high growth potential. A professional musician who has mastered their instrument, on the other hand, has considerable skill but limited growth potential.

Similarly, a starting company with only basic quality measures in place could implement large-scale improvement initiatives and reap massive rewards. In contrast, a near-perfect company would make incremental improvements and realize limited value. The latter does not benefit from extensive, rock-the-boat changes; in fact, such efforts could prove to be counterproductive. Executives who plot themselves on the asymptote graph can more accurately evaluate whether they should implement large-scale improvement measures or take a more measured approach.

Quality initiatives need to suit an organization’s unique needs. While improvement measures can provide enormous value, they will only do so if they are strategically sized and implemented. Prioritizing quality can’t backfire; however, prioritizing quality for quality’s sake and at the expense of employee morale will. Careful initiative development is a must.

Not sure how to design your organization’s improvement strategy? Download Gerent’s most recent white paper, Is It Possible to “Overdo” Quality?, for a primer on how to develop high-potential quality initiatives!